The long curtains draw back to reveal a high-ceilinged hall. Its walls are lined with drapes made of hundreds of jute bags sewed together. Their mouldy, raw fragrance wafts through the room, and the old fans squeak at every slow, forced rotation. Three continuous rows of chairs border the room. They vary in shape and size, placed at equal intervals.

The brown room is oddly familiar and therefore cosy. It’s the kind of place where you want to sit quietly, staring at nothing. My meditation is interrupted when Ghanian artist Ibrahim Mahama walks in. Dressed in all pink, the man who topped 2025’s Art Review Power 100 list takes a seat in the middle of the room. There is a certain authority in his gait as he greets the first few viewers of the day at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2025-2026). It is, after all, his creation at one of the most anticipated contemporary art event in India, and it’s titled The Parliament of Ghosts.

The installation explores colonialism, its shared history, global trade and labour exploitation through salvaged, everyday materials. It creates a physical space for reflection on erased histories of exploitation during colonialism and the trade practices that were used then. “The work aims at looking at the process, its political conditioning, the idea of repair and found material,” says Mahama. In Kochi, he worked with local women, who sourced the jute bags from the city, one of the oldest ports in the world, and stitched them together. In Ghana the made-in-India bags are used to store and import goods, observes Mahama. That makes for a shared material history.

The chairs too were found in Kochi and repaired by local carpenters. Mahama put up a large television in the space while it was being built to explain to student volunteers the process of his creation and the idea behind his work. In return for their labour, he viewed each of their portfolios and reviewed them. “The idea was to create together, in collaboration with others and with available resources,” he says.

That practice is the crux of‘For the Time Being, the theme of this biennale that has been curated by performance artist Nikhil Chopra and HH Art Spaces, the artist collective that he co-founded in Goa. “The exhibition moves away from a finished spectacle toward a living, evolving, and performance-based ecosystem,” says Chopra. “The sixth edition is an invitation to embrace process as methodology, and to place the friendship economies that have long nurtured artist-led initiatives as the very scaffolding of the exhibition,” he adds.

In essence, the works evolve as days pass, as more viewers experience and participate in them. Chopra’s curation prioritises collaboration, trust, shared resources, and mutual support among artists, workers, and the local community. And that, I am happy to report, is certainly visible in the biennale’s 66 main projects spread across 22 venues, by artists across 25 countries including Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, Germany, Kenya, Palestine, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, among others.

New-York-based Nari Ward’s Divine Smiles is a perfect example. His project begins with a pushcart that is taken to different places across Fort Kochi. People passing by are encouraged to smile while looking at two small tin boxes with a mirrored base. As participants see themselves smile in the box, an old-style can sealer with a rotating wheel, placed on the cart, seals them both, in a way of locking in smiles. One tin is given to the participant as a keep-sake and another is stuck on a huge magnetic ball at Anand Warehouse. Each tin adds more glass and light to the ball, making it look like a big disco ball of happiness. “The idea is to transform a fleeting, everyday human expression into a lasting, shared monument of community resilience and positive human connection,” explains Ward.

Beyond participative installations, the other big presence at the biennale is that of performative art. Among the most noteworthy is Marina Abramović’s work, a three-channel video installation titled Waterfall (2000–03). Known for pushing the boundaries of performance art, Abramović started her career in Serbia in the 1970s. Waterfall is a large video installation that shows the faces of 120 Tibetan monks and nuns from five different Buddhist schools chanting the Heart Sutra (A Buddhist text) in unison. Abramović shot the footage at the Sacred Music Festival in Bangalore in the year 2000. All the simultaneous chanting creates a sound similar to that of a waterfall, which fills the exhibition space at Willingdon Island. Viewers are invited to sit in deckchairs, placed on sand, facing the monumental screen to immerse themselves in the film and take a break from the digital overload of modern life, even if only for a short while.

Then, there is The Panjeri Artists’ Union’s installation spanning a couple of rooms at the Aspinwall House, one of the biennale’s main venues. The collective of artists, activists, and academics from Kolkata presents an exhibition that traces the common history of Kochi and Bengal. The showcase unfolds in parts over days and features protest posters, slogans, and charcoal drawings depicting bodies and faces, and handwoven textiles made by displaced labourers. It’s also a site for performance. In one of the acts, an artist draws chalk lines only to have them erased by another, visually representing the ongoing processes of creation and erasure.

While discussing the process of creation, Jayashree Chakravarty’s work stands out. She has spent almost a year to create a monumental installation called Shelter: For the Time Being. It’s one of those works that you can’t tire of looking at. When you stroll through the dimly-lit room and look at the work that stretches from floor to ceiling with your phone’s torchlight, you see so many different things: weeds, twigs, grass, seeds, roots, insects gathered and blanketed between layers of translucent sheaths of paper, all completely handmade by Chakravarty. “That’s my practice. I find it meditative to create with hands. I have created every tiny element of the work myself,” she says. Her work records the patterns and continuities of the natural world. “Nature is our primal shelter where all beings may feel welcome and take rest,” she says. “It has always protected and nurtured us. Though, here I have cocooned it inside the larger installation to show how, today, it needs protection from us.”

Another meticulous work is Smita M Babu’s Paakkalam, a painting and performative project, which features her finely detailed, beautiful watercolours of the landscape by the lakes of Kollam, her hometown, which is a traditional coir-making area in Kerala. The paintings explore paakkalam, Malyalam for weaving workspace. Tiny human figures, dressed in white, surrounded by coconut trees, stand in a circle, stretching out choir threads, zig-zagged and intertwined with the dance-like, acrobatic movements of the humans. Elsewhere, a labourer carries a huge cloud of brown ropes on his head, while little girls in pink play with a cycle tire, rotating it with a stick. These layered images in earthy tones documenting the everyday life of Kollam are gorgeous to look at. “My project merges my background in visual and theatre arts to document the labour, memory, and lived experiences of Kollam’s traditional coir-making community,” says Babu. The site-responsive work, drawn from her life growing up along the Ashtamudi Lake also encompasses a performance that reimagines coir-making as a poetic movement ritual. It highlights the dignity of manual labour and the community life surrounding the coir industry, aligning with the biennale’s curatorial theme of friendship economies and valuing process and shared resources.

Among the other works that caught my attention were Prabhakar Kamble’s Vichitra Natak (Theatre of the Absurd) and Brazilian artist Cinthia Marcelle’s participatory project and installation History (version Mattancherry).

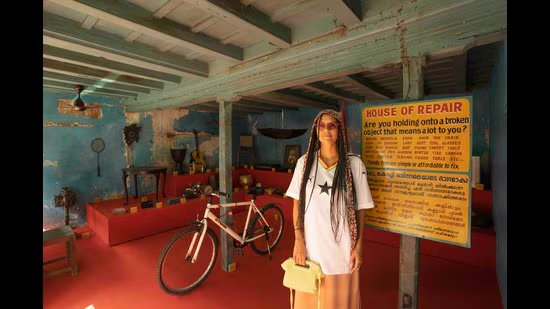

Marcelle’s is a house of repair. She invited Kochi residents to give her their cherished broken items. She then found people who could repair them in Mattancherry, a harbour on the world trade route, dating back to 1341 CE. The fixed items are now placed in a temporary space, made to look like an old shop, in the neighbourhood. The element of surprise here is that she managed to find people, whom she refers to as artisans, who could repair manual calculators which look like typewriters with just 13 keys. There is a small golden steam iron too; a vinyl recorder encased in a black suitcase, an umbrella, a washing machine, a tabla and more. Some of these are over a hundred years old. The project challenges the “capitalist logic” of constant consumption and replacement by highlighting the value of keeping and repairing items that carry personal history and memory, emphasizing the importance of community, shared resources, and the often-invisible labour of artisans. All of these objects will be returned to their owners after the biennale.

Kamble’s work highlights the works of Dalit labourers. He uses ropes, textiles, metal scraps etc to make his multi-part installations, which talk about caste annihilation. “If you really want equity, we must push for case annihilation,” he says, adding “Ambedkar had said that when art is segregated according to caste, it’s a disservice to it.”

The sixth edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale is an attempt to transgress those boundaries; the old, restrictive codes of making art and looking at the world. It creates a space that is collective, collaborative and inclusive.

Riddhi Doshi is an independent journalist.